The yield on the 30-year US Treasury bond, a key indicator of long-term borrowing costs, has soared to its highest level since 2010, as investors brace for higher inflation and interest rates.

What is driving the bond sell-off?

The bond market has been under pressure for several months, as the Federal Reserve signaled that it will keep its benchmark interest rate near zero until at least 2025, despite rising inflation and economic growth. The Fed’s policy stance has eroded the appeal of bonds, which offer fixed payments over time, and prompted investors to seek higher returns elsewhere.

In addition, the US government has ramped up its borrowing to fund its massive stimulus spending, which has boosted the supply of bonds and lowered their prices. The US Treasury Department plans to issue $1.4 trillion of debt in the second half of 2023, up from $1.1 trillion in the first half.

Another factor that has weighed on the bond market is the downgrade of the US credit rating by Fitch Ratings, which cited the country’s deteriorating fiscal outlook and political gridlock. Fitch lowered the US rating from AAA to AA+ on September 15, following a similar move by Standard & Poor’s in 2011.

Finally, the surge in oil prices, which have reached their highest level since 2014, has fueled inflation expectations and reduced the real value of bond payments. Oil prices have risen more than 50% this year, driven by strong demand, supply disruptions and geopolitical tensions.

How high can the long-bond yield go?

The yield on the 30-year Treasury bond, which moves inversely to its price, has jumped about 85 basis points since the end of June, reaching 4.81% on Thursday, the highest level since October 2010. A basis point is one-hundredth of a percentage point.

Some analysts and investors expect the long-bond yield to climb even higher, as the bond market adjusts to the changing economic and financial environment. Bill Ackman, the founder and CEO of Pershing Square Capital Management, said he would not be shocked to see the 30-year Treasury yield well into the 5% range, during an interview with CNBC on Thursday.

Ackman said that the bond market is in a “bubble” and that investors are underestimating the risk of inflation and interest rate hikes. He said that he is betting against the bond market by buying credit default swaps, which are contracts that pay off if a borrower defaults on its debt.

Other market participants are more cautious, saying that the bond sell-off may be overdone and that the long-bond yield could stabilize or even fall in the coming months. They point to the fact that the US economy is still facing some headwinds, such as the ongoing pandemic, the labor shortage, the supply chain bottlenecks and the potential government shutdown.

They also argue that the Fed has the tools and the willingness to intervene in the bond market if needed, by increasing its bond purchases or implementing a policy known as yield curve control, which aims to cap the yields of certain maturities.

What are the implications of the rising long-bond yield?

The rising long-bond yield has significant implications for the economy and the financial markets, as it affects the cost of borrowing and the valuation of assets.

For the government, the higher long-bond yield means that it will have to pay more interest on its debt, which could widen the budget deficit and limit its fiscal space. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the US federal debt held by the public will reach 107% of gross domestic product by the end of 2023, the highest level since World War II.

For the corporate sector, the higher long-bond yield could increase the cost of financing and reduce the profitability of some businesses, especially those that rely heavily on debt or have long-term projects. The higher long-bond yield could also make it harder for some companies to refinance their maturing debt, which could increase the risk of default and bankruptcy.

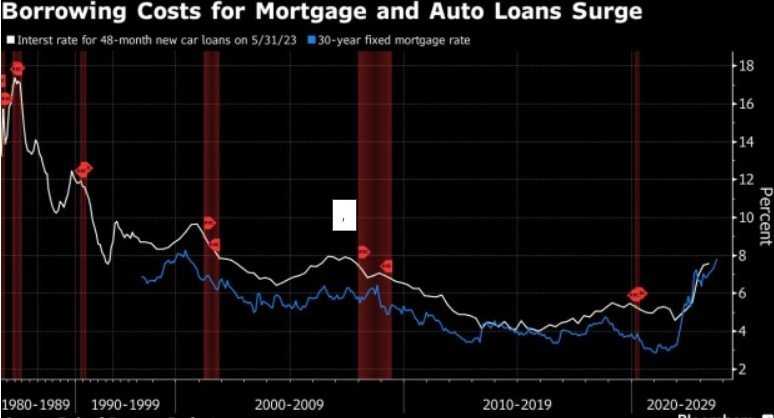

For the household sector, the higher long-bond yield could raise the cost of mortgages, student loans, car loans and other forms of consumer credit, which could dampen the demand for housing and durable goods. The higher long-bond yield could also reduce the wealth effect of rising stock and home prices, which could weigh on consumer confidence and spending.

For the financial sector, the higher long-bond yield could create volatility and uncertainty in the markets, as investors adjust their portfolios and expectations. The higher long-bond yield could also trigger a sell-off in other asset classes, such as stocks, corporate bonds, emerging-market debt and commodities, which could lead to losses and contagion.